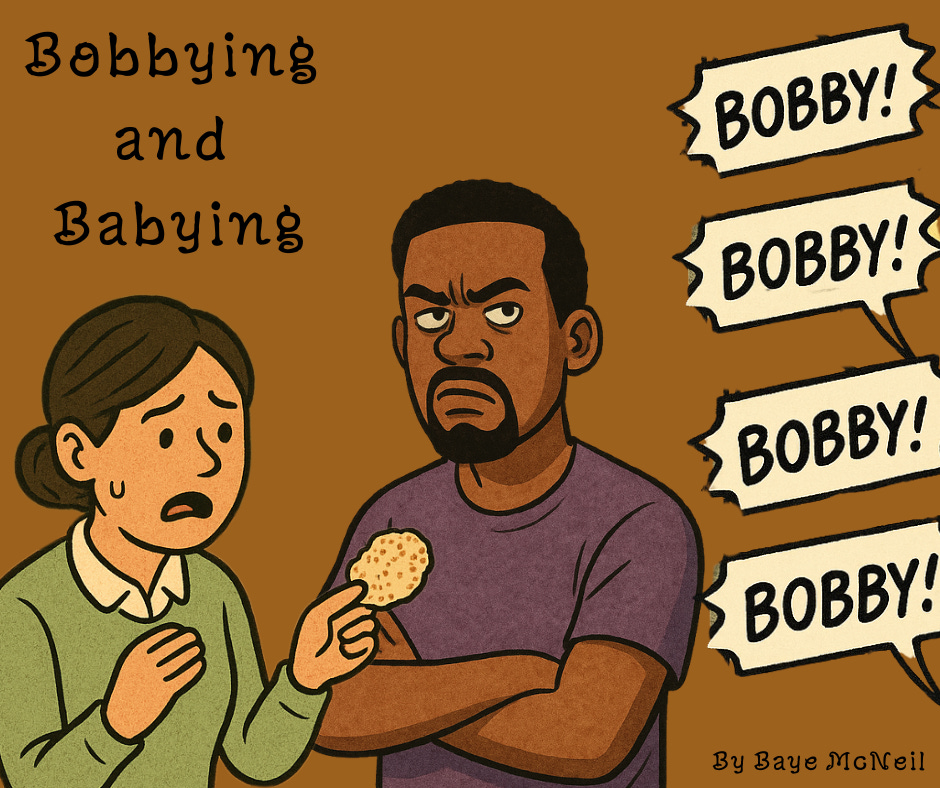

Bobbying and Babying: Life in a Japanese Teacher’s Office

After 20 years in Japan, I can eat a cracker without assistance. But that doesn’t stop the infantilization—or the kids in the hallway calling me Bobby.

The teacher seated next to me (Tonari-Sensei) at this week’s school looks uptight now.

Not Western uptight. She’s got the Japanese skill of looking unbothered—even when she’s stiff as a board. But anyone who can read the air can see she’s tense AF.

It’s my fault, kinda. Let me explain…

This school had been waiting several weeks for my arrival. So the teachers and students had plenty of time to dust off and roll out the red carpet, so to speak, and I must say—it felt rather nice.

So nice that I even contemplated, for a second, letting this woman infantilize and gaijin me to show my appreciation.

For a hot second.

Unfortunately, some Japanese people cannot control the impulse to incessantly introduce the most basic aspects of their culture to you. She was one of them. Point blank, you could tell this person you’ve lived among them for 20 years, and it wouldn’t register. You could snark,

“In those two decades, yes, I think I might’ve heard one or two people say otsukaresamadesu once or twice,” and your sarcasm would bounce off like a rubber dart.

You’re a foreigner. Which, to them, means a tourist for life. Tenure is immaterial.

“Assume the foreigner’s utter ignorance and educate them whenever possible” is the prime directive. That message starts early. Even grade school English textbooks are geared toward it. The Japanese characters constantly introduce the uniqueness of Japan to the non-Japanese ones.

Like:

“Hi, Cindy! Would you like to go to a Japanese shrine with me?

We can enjoy a Japanese tea ceremony.

Then we can drink Japanese tea and enjoy Japanese snacks.

Have you ever had Japanese green tea?

There are many Japanese cherry blossom trees, too.

The Japanese culture there is so beautiful because we have four seasons.

Shall we go and enjoy it together?”

I fantasize about having the foreign character say:

“Uh, yeah, no. Ha—rd pass. No offense, but I’ve enjoyed about as much Japanese culture as I can

stomachenjoy in onefuckingJapanese day. Tomorrow might work, though. Or maybe during one of your other three Japanese seasons. I still can’t believe you guys actually have four. Wow. Anyway, let’s play it by ear, shall we?”

Still, I used to play the expected “ignorant foreigner forever” role and let them get this compulsion out of their system. It is, by far, the path of least resistance.

But goddammit, I couldn’t do it. I wanted to. But if you open that door even a crack, there’s no shutting it, and before you can say “Takadanobaba,” the whole school will be Bobbying and babying you all day, every day.

The babying, I decided to head off at the pass. It won’t stop the students, but I might be able to establish a limited No-Babying Baye Zone in the teachers’ office. And that’s better than nothing. Otherwise, there’d be no respite from it.

But the Bobbying… that’s a whole other thing.

Bobbying refers to the compulsion to associate me with whoever happens to be the darker-hued darling of Japan’s pop imagination. Over the years, I’ve been seen as Bob Sapp, Billy Blanks, Bobby Ologun, even Jero and Barack Obama. But Bobby Ologun is the one that stuck.

Hence: Bobbying.

Anyway, Tonari-Sensei was appointed point person. Gaijin Inquisitor.

Her duties:

Handle all English inquiries

Keep the Nippon neophyte (me) “well-behaved”

Ensure communication went smoothly

I’m guessing she got stuck with the role weeks before I showed up. How?

The time-honored Japanese method of decision-making: Janken (rock-paper-scissors).

I can picture it now—English teachers huddled in the staff room, whispering prayers and sweating through their shirts and blouses:

“Fingers, don’t fail me now…”

No shame in their game.

The loser, Tonari, got stuck with me.

With a thousand-volt smile, Tonari-Sensei said in passable English:

“Need you something let know. OK?”

“Thanks, but I’m copacetic!” I replied in passable Japanese.

Her grin dimmed—from 1000 volts to just enough to light a penlight. But she stuck with the English. And I responded to every English inquiry in Japanese.

This persistence made her uncomfortable. My kicking open the lid of the box she’d so courteously and painstakingly prepared for the “me” she imagined I'd be every time she tried to affix it shut with duct tape, pushed her gaman (patience) to its limits.

And I felt almost bad about it.

Almost.

Around lunchtime, another teacher approached with some osembei (Japanese rice crackers) she’d brought back as souvenirs. But instead of speaking to me directly, she went through the designated gaijin-whisperer, Tonari.

Sembei-sensei (in Japanese): I want to offer our foreign guest some sembei. How do I say it?

Tonari-sensei: Just say, “Can you eat Japanese snacks?”

Me (in Japanese): Yes, I can! I like osembei very much. And I speak Japanese a little, so you can talk to me directly if you'd like.

Sembei-sensei (to Tonari): Oh, can he speak Japanese?

Tonari-sensei (to her): Maybe. I think.

Sembei-sensei (to me, using broken English and finger-to-mouth gestures): Can eat Japanese snack?

Me (in Japanese, as politely as I could): Please feel free to use Japanese. If I don’t understand, I’ll ask Tonari-Sensei—I promise. She wants to help. But your English is hard to understand.

She bowed and apologized, then gave me a cracker.

Tonari shot me a dirty look on the low.

Then she re-applied her politeness mask and tried again.

Tonari-sensei (in English): You can eat Japanese snacks?

Me (in Japanese): You heard me tell Sembei-sensei I like Japanese crackers very much, didn’t you? Or is my Japanese that poor?

She understood me just enough to be taken aback by the rebuff.

But she stood her ground.

外人は外人だ

A foreigner is a foreigner.

And I stood mine.

幼児化するな

Don’t treat me like a child.

I opened the crackers and took a bite. Hopefully, the crunch said all I needed to but dared not say.

When the lunch bell rang, I think she decided to make peace.

Or maybe she was just hungry.

Either way, as we ate lunch side by side, I said to her, in Japanese:

“I appreciate your intention to make me feel comfortable. I really do.

But I’d appreciate it more if you made me feel at home.

Here. In my home of 20 years. You know?”すみません, My bad, Tonari said, and bowed. “これから日本語だけで話…”

From now on in Japanese only—

ペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラペラ...

I couldn’t make heads or tails of what she’d said.

“Sorry—could you repeat that in English?” I said.

And we both laughed. Hard.

From the hallway, I could hear students crying out:

“Bobby! Bobby!”

They meant me.

This is an excerpt from my latest book, “Words by baye, Art by Miki.” If you dig this story, you’ll LOVE the book! Pick up a signed copy here:

‘Can you use chopsticks?’ And in reply, ‘Can you use a spoon?’

Thanks for sharing bro! I love your names for things, ‘Bobbying’ and Tonari-sensei. I always get Tom Cruise, should it be called ‘Tommying’ or ‘Crusing’

I’d forgotten just how many of these exact same encounters I navigated in Japan. “Can you eat Japanese food?” “Can you use chopsticks?” And the side eye when you don’t neatly fit into the box they’ve made for you.